Elizabeth Warren makes a compelling case against the Trans-Pacific Partnership in The Trans-Pacific Partnership clause everyone should oppose, where she says:

…

ISDS [Investor-State Dispute Settlement] would allow foreign companies to challenge U.S. laws — and potentially to pick up huge payouts from taxpayers — without ever stepping foot in a U.S. court. Here’s how it would work. Imagine that the United States bans a toxic chemical that is often added to gasoline because of its health and environmental consequences. If a foreign company that makes the toxic chemical opposes the law, it would normally have to challenge it in a U.S. court. But with ISDS, the company could skip the U.S. courts and go before an international panel of arbitrators. If the company won, the ruling couldn’t be challenged in U.S. courts, and the arbitration panel could require American taxpayers to cough up millions — and even billions — of dollars in damages.

If that seems shocking, buckle your seat belt. ISDS could lead to gigantic fines, but it wouldn’t employ independent judges. Instead, highly paid corporate lawyers would go back and forth between representing corporations one day and sitting in judgment the next. Maybe that makes sense in an arbitration between two corporations, but not in cases between corporations and governments. If you’re a lawyer looking to maintain or attract high-paying corporate clients, how likely are you to rule against those corporations when it’s your turn in the judge’s seat?

…

The use of ISDS is on the rise around the globe. From 1959 to 2002, there were fewer than 100 ISDS claims worldwide. But in 2012 alone, there were 58 cases. Recent cases include a French company that sued Egypt because Egypt raised its minimum wage, a Swedish company that sued Germany because Germany decided to phase out nuclear power after Japan’s Fukushima disaster, and a Dutch company that sued the Czech Republic because the Czechs didn’t bail out a bank that the company partially owned. U.S. corporations have also gotten in on the action: Philip Morris is trying to use ISDS to stop Uruguay from implementing new tobacco regulations intended to cut smoking rates.

…

I understand Senator Warren’s focus on the United States, but it diverts her from a darker issue raised by the TPP.

The TPP gives international investors sovereignty equivalent to national governments.

Without the TPP and similar agreements, an international investor with a dispute with Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Singapore,United States, Vietnam, or New Zealand, has to sue in the courts of that country.

With the TPP, international investors being equal sovereigns with those countries, can use Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) to bring a national government before privately selected arbiters, in possibly secret proceedings, because of laws or regulations they find objectionable.

Is that scare mongering?

Why don’t you ask:

Australia. Phillip Morris is suing Australia over legislation to regulate tobacco packaging. The Australian government has assembled all the public documents from that process at: Tobacco plain packaging—investor-state arbitration. The proceedings are based on: (Hong Kong – Australia treaty) (I have read predatory agreements before but nothing on this scale. There are no limits on the rights of investors. None at all.)

Or,

Uruguay. Phillip Morris is suing Uruguay because of laws that has been reducing smoking by 4.3% a year.

(Philip Morris Sues Uruguay Over Graphic Cigarette Packaging) Not in court, a Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) proceeding. This proceeding is based on: (The Swiss Confederation – Uruguay Bilateral Trade Agreement)

The Uruguay agreement provides in part:

…

Article 2 Promotion, admission

(1) Each Contracting Party shall in its territory promote as far as possible investments by investors of the other Contracting Party and admit such investments in accordance with its law. The Contracting Parties recognize each other’s right not to allow economic activities for reasons of public security and order, public health or morality, as well as activities which are by law reserved to their own investors.

…

That sounds like a public health exception to me.

If the United States and the other countries are daft enough to confer sovereignty on international investors, are there any limits to their rights?

From the TPP:

…

3 (b) Non-discriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety, and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations, except in rare circumstances. [TPP Annex II-B]

I don’t know what “rare circumstances” might mean in this context so I wrote to the Office of the United States Trade Representative at: correspondence@ustr.eop.gov, on March 28, 2015, saying:

I am trying to follow the discussion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement

and have a question about Annex 11-B paragraph 3, sub-point (b), which reads:

*****

Non-discriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied

to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety,

and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations, except in rare

circumstances.

*****

My question is: Have there been any cases of "rare circumstances?"

I assume from the wording not many but that it is mentioned at all

implies it isn't unknown.

Is there are source for decisions that would include those "rare

circumstances" that is available online?

Or other sources though those would be difficult for me to consult

since I don't travel. Perhaps I could request copies of such decisions.

Thanks!

I can quote the response of the Office of the United States Trade Representative in full:

That’s right, no response at all.

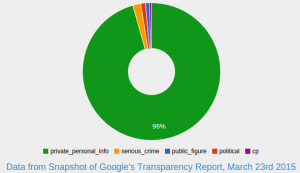

The Phillip Morris cases are concrete evidence of how investment treaties as used in fact to over turn public health laws passed by a sovereign government.

Why should the United States, or any other country need confer sovereignty on international investors, so they can have a very private court between themselves and nation states?

The United States has fine courts open for litigation. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals recently ruled the NSA bulk collection of domestic calling records to be unconstitutional. I don’t think anyone can truthfully say that the U.S. government has an unfair advantage in U.S. courts.

As a matter of fact, there is a free trade agreement with Australia Section 11 Investment, that has no Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) language at all.

The most it says is found in Article 11.5 Minimum Standard of Treatment, 2. (a):

“fair and equitable treatment” includes the obligation not to deny justice in criminal, civil, or administrative adjudicatory proceedings in accordance with the principle of due process embodied in the principal legal systems of the world; and

If investors from either country has a problem, they can sue in the courts of the other country. That was at the instigation of Australia as I understand the back story on that agreement.

Adoption of the TPP will mean that six hundred and forty five million (645) people (estimates for 2015), who produce forty (40%) percent of the world GDP, will be ruled over by their governments and an unknown number of unelected international investors.

Other resources to consult:

United Nations Conference on Trade and Agreement

Investor-state dispute settlement: A sequel (UNCTAD Series on Issues in International Investment Agreements II)

At page 52 it comments on non-discriminatory regulations (public health for example), saying:

…

IIAs’ substantive obligations can be delineated by general exceptions. The latter allow States to derogate from the IIA obligations when such derogation pursues a policy objective included in the general-exceptions clause. Such policy may include public health and safety, national security, environmental protection and some others. A number of treaties now contain general exceptions, but how they will work in practice is yet to be tested.

…

Claims by TPP supporters that the TPP will not impact national laws is at best disingenuous and at worse an outright lie. No one really knows how far sovereignty granted to international investors will go under the TPP language.

Issues in International Investment Agreements (First series)UNCTAD

Thirty five (35) documents that cover investment agreements in great detail. This is part of the second series referenced in Investor-state dispute settlement: A sequel (UNCTAD Series on Issues in International Investment Agreements II).

One volume of particular interest: Expropriation, at pages 57-109.

…

II. Establishing An Indirect Exprorpriation and Distinguishing It From Noncompensable Regulation.

The matter of establishing an indirect expropriation without impeding the right of States to regulate in the public interest has been one of the more challenging problems in recent years. This section aims to review the relevant treaty and arbitral practice and contribute to the development of an appropriate analytical framework.

Section A examines the factors used to evaluate whether an indirect expropriation has occurred. These include assessing the impact on the investment, interference with investor’s legitimate expectations and the characteristics of the measure at stake.

Section B discusses how IIAs have singled out noncompensable regulatory measures and distinguishes them from cases of indirect expropriation. Such measures do not require compensation even where they produce a significant negative effect on an investment.

Section C concludes the preceding discussion by providing a framework for analysis of whether a certain governmental measure constitutes an indirect expropriation.

…

I lack the author’s confidence that the police powers of the state will be respected, particularly in light of the “practice” of international investors as shown by Phillip Morris.

International Investment Agreements Navigator A very useful resource for finding international investment agreements.