Genomeweb posted this summary of Stuart Firestein’s op-ed on failure to replicate:

Failure to replicate experiments is just part of the scientific process, writes Stuart Firestein, author and former chair of the biology department at Columbia University, in the Los Angeles Times. The recent worries over a reproducibility crisis in science are overblown, he adds.

“Science would be in a crisis if it weren’t failing most of the time,” Firestein writes. “Science is full of wrong turns, unconsidered outcomes, omissions and, of course, occasional facts.”

Failures to repeat experiments and the struggle to figure out what went wrong has also fed a number of discoveries, he says. For instance, in 1921, biologist Otto Loewi studied beating hearts from frogs in saline baths, one with the vagus nerve removed and one with it still intact. When the solution from the heart with the nerve still there was added to the other bath, that heart also slowed, suggesting that the nerve secreted a chemical that slowed the contractions.

However, Firestein notes Loewi and other researchers had trouble replicating the results for nearly six years. But that led the researchers to find that seasons can affect physiology and that temperature can affect enzyme function: Loewi’s first experiment was conducted at night and in the winter, while the follow-up ones were done during the day in heated buildings or on warmer days. This, he adds, also contributed to the understanding of how synapses fire, a finding for which Loewi shared the 1936 Nobel Prize.

“Replication is part of [the scientific] process, as open to failure as any other step,” Firestein adds. “The mistake is to think that any published paper or journal article is the end of the story and a statement of incontrovertible truth. It is a progress report.”

You will need to read Firestein’s comments in full: just part of the scientific process, to appreciate my concerns.

For example, Firestein says:

…

Absolutely not. Science is doing what it always has done — failing at a reasonable rate and being corrected. Replication should never be 100%. Science works beyond the edge of what is known, using new, complex and untested techniques. It should surprise no one that things occasionally come out wrong, even though everything looks correct at first.

…

I don’t know, would you say an 85% failure to replicate rate is significant? Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research, C. Glenn Begley & Lee M. Ellis, Nature 483, 531–533 (29 March 2012) doi:10.1038/483531a. Or over half of psychology studies? Over half of psychology studies fail reproducibility test. just to name two studies on replication.

I think we can agree with Firestein that replication isn’t at 100% but at what level are the attempts to replicate?

From what Firestein says,

“Replication is part of [the scientific] process, as open to failure as any other step,” Firestein adds. “The mistake is to think that any published paper or journal article is the end of the story and a statement of incontrovertible truth. It is a progress report.”

Systematic attempts at replication (and its failure) should be part and parcel of science.

Except…, that it’s obviously not.

If it were, there would have been no earth shaking announcements that fundamental cancer research experiments could not be replicated.

Failures to replicate would have been spread out over the literature and gradually resolved with better data, methods, if not both.

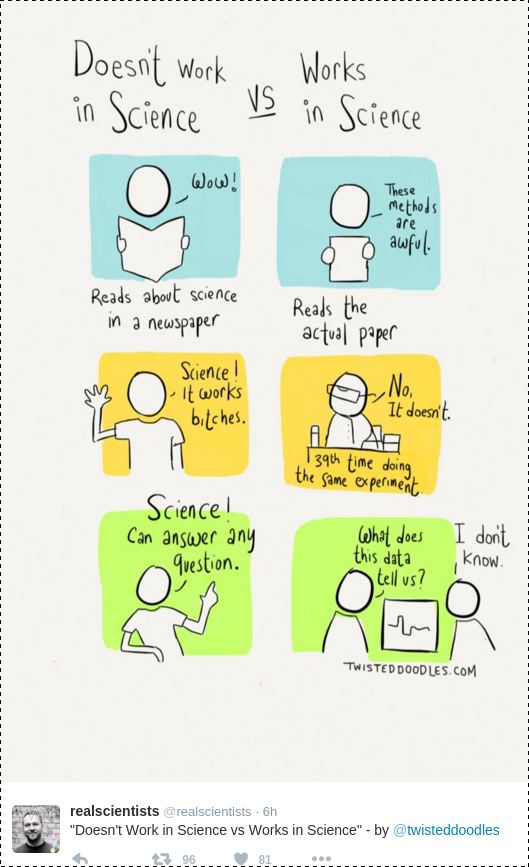

Failure to replicate is a legitimate part of the scientific method.

Not attempting to replicate, “I won’t look too close at your results if you don’t look too closely at mine,” isn’t.

There an ugly word for avoiding looking too closely at your own results or those of others.