Alda: A Manifesto and Gentle Introduction by Dave Yarwood.

From the webpage:

What is Alda?

Alda’s ambition is to be a powerful and flexible music programming language that can be used to create music in a variety of genres by typing some code into a text editor and running a program that compiles the code and turns it into sound. I’ve put a lot of thought into making the syntax as intuitive and beginner-friendly as possible. In fact, one of the goals of Alda is to be simple for someone with little-to-no programming experience to pick up and start using. Alda’s tagline, a music programming language for musicians, conveys its goal of being useful to non-programmers.

But while its syntax aims to be as simple as possible, Alda will also be extensive in scope, offering composers a canvas with creative possibilities as close to unlimited as it can muster. I’m about to ramble a little about the inspiring creative potential that audio programming languages can bring to the table; it is my hope that Alda will embody much of this potential.

At the time of writing, Alda can be used to create MIDI scores, using any instrument available in the General MIDI sound set. In the near future, Alda’s scope will be expanded to include sounds synthesized from basic waveforms, samples loaded from sound files, and perhaps other forms of synthesis. I’m envisioning a world where programmers and non-programmers alike can create all sorts of music, from classical to chiptune to experimental soundscapes, using only a text editor and the Alda executable.

In this blog post, I will walk you through the steps of setting up Alda and writing some basic scores.

…

Whether you want to create new compositions or be able to “hear” what you can read in manuscript form, this looks like an exciting project.

A couple of resources if you are interested in historical material:

The Morgan Library &: Museum’s Music Manuscripts Online, which as works by J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Debussy, Fauré, Haydn, Liszt, Mahler, Massenet, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Puccini, Schubert, and Schumann, and others.

Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM).

The sources archived include all the currently known fragmentary sources of polyphony up to 1550 in the UK (almost all of these are available for study through this website); all the ‘complete’ manuscripts in the UK; a small number of important representative manuscripts from continental Europe; a significant portion of fragments from 1300-1450 from Belgium, France, Italy, Switzerland and Spain. Such a collection of images, created under strict protocols to ensure parity across such a varied collection, has never before been possible, and represents an extraordinary resource for study of the repertory as a whole. Although these manuscripts have been widely studied since their gradual discovery by scholars at various times over the past century, dealing with the repertory as a whole has been hampered by the very wide geographical spread of the manuscripts and the limitations of microfilm or older b/w photography. Fragments are far more numerous than complete sources, but most of them are the sole remaining representatives of lost manuscripts. Some are barely legible and hard to place and interpret. They amount to a rich but widely scattered resource that has been relatively neglected, partly because of difficulty of access, legibility and comparison of materials that are vulnerable to damage and loss.

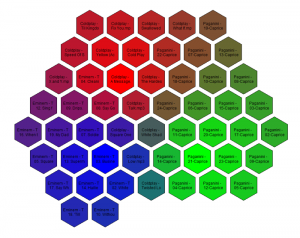

Being aware, of course, that music notation has evolved over the years and capturing medieval works will require mastery of their notations.

A mapping from any form of medieval notation to Alda I am sure would be of great interest.