Serendipity in the Stacks: Libraries, Information Architecture, and the Problems of Accidental Discovery by Patrick L. Carr.

Abstract:

Serendipity in the library stacks is generally regarded as a positive occurrence. While acknowledging its benefits, this essay draws on research in library science, information systems, and other fields to argue that, in two important respects, this form of discovery can be usefully framed as a problem. To make this argument, the essay examines serendipity both as the outcome of a process situated within the information architecture of the stacks and as a user perception about that outcome.

A deeply dissatisfying essay on serendipity as evidenced in the author’s conclusion that reads in part:

While acknowledging the validity of Morville’s points, I nevertheless believe that, along with its positive aspects, serendipity in the stacks can be usefully framed as a problem. From a process-based standpoint, serendipity is problematic because it is an indicator of a potential misalignment between user intention and process outcome. And, from a perception-based standpoint, serendipity is problematic because it can encourage user-constructed meanings for libraries that are rooted in opposition to change rather than in users’ immediate and evolving information needs.

To illustrate the “…potential misalignment between user intention and process outcome,” Carr uses the illustration of a user looking for a specific volume by call number but the absence of the book for its location, results in the discovery of an even more useful book nearby. That Carr describes as:

Even if this information were to prove to be more valuable to the user than the information in the book that was sought, the user’s serendipitous discovery nevertheless signifies a misalignment of user intention and process outcome.

Sorry, that went by rather quickly. If the user considers the discovery to be a favorable outcome, why should we take Carr’s word that it “signifies a misalignment of user intention and process outcome?” What other measure for success should an information retrieval system have other than satisfaction of its users? What other measure would be meaningful?

Carr refuses to consider how libraries could seem to maximize what is seen as a positive experience by users because:

By situating the library as a tool that functions to facilitate serendipitous discovery in the stacks, librarians risk also situating the library as a mechanism that functions as a symbolic antithesis to the tools for discovery that are emerging in online environments. In this way, the library could signify a kind of bastion against change. Rather than being cast as a vital tool for meeting discovery needs in emergent online environments, the library could be marginalized in a way that suggests to users that they perceive it as a means of retreat from online environments.

I don’t doubt the same people who think librarians are superflous since “everyone can find what they need on the Internet” would be quick to find libraries as being “bastion[s] against change.” For any number of reasons. But the opinions of semi-literates should not dictate library policy.

What Carr fails to take into account is that a stacks “environment,” which he concedes does facilitate serendipitous discovery, can be replicated in digital space.

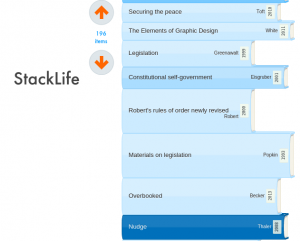

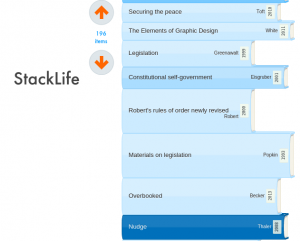

For example, while it is currently a prototype, StackLife at Harvard is an excellent demonstration of a virtual stack environment.

Jonathan Zittrain, Vice-Dean for Library and Information Resources, Harvard Law School; Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Professor of Computer Science at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences; Co-founder of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society, nominated StackLife for Stanford Prize for Innovation in Research Libraries, saying in part:

- It always shows a book (or other item) in a context of other books.

- That context is represented visually as a scrollable stack of items — a shelf rotated so that users can more easily read the information on the spines.

- The stack integrates holdings from multiple libraries.

- That stack is sorted by “StackScore,” a measure of how often the library’s community has used a book. At the Harvard Library installation, the computation includes ten year aggregated checkouts weighted by faculty, grad, or undergrad; number of holdings in the 73 campus libraries, times put on reserve, etc.

- The visualization is simple and clean but also information-rich. (a) The horizontal length of the book reflects the physical book’s height. (b) The vertical height of the book in the stack represents its page count. (c) The depth of the color blue of the spine indicates its StackScore; a deeper blue means that the work is more often used by the community.

- When clicked, a work displays its Library of Congress Subject Headings (among other metadata). Clicking one of those headings creates a new stack consisting of all the library’s items that share that heading.

- If there is a Wikipedia page about that work, Stacklife also displays the Wikipedia categories on that page, and lets the user explore by clicking on them.

- Clicking on a work creates an information box that includes bibliographic information, real-time availability at the various libraries, and, when available: (a) the table of contents; (b) a link to Google Books’ online reader; (c) a link to the Wikipedia page about that book; (d) a link to any National Public Radio audio about the work; (e) a link to the book’s page at Amazon.

- Every author gets a page that shows all of her works in the library in a virtual stack. The user can click to see any of those works on a shelf with works on the same topic by other authors.

- Stacklife is scalable, presenting enormous collections of items in a familiar way, and enabling one-click browsing, faceting, and subject-based clustering.

Does StackLife sound like a library “…that [is] rooted in opposition to change rather than in users’ immediate and evolving information needs.”

I can’t speak for you but it doesn’t sound that way to me. It sounds like a library that isn’t imposing its definition of satisfaction upon users (good for Harvard) and that is working to blend the familiar with new to the benefit of its users.

We can only hope that College & Research Libraries will have a response from the StackLife project to Carr’s essay in the same issue.

PS: If you have library friends who don’t read this blog, please forward a link to this post to their attention. I know they are consumed with their current tasks but the StackLife project is one they need to be aware of. Thanks!

I first saw the essay on Facebook in a posting by Simon St.Laurent.