Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color by Sarah E. Bond.

From the post:

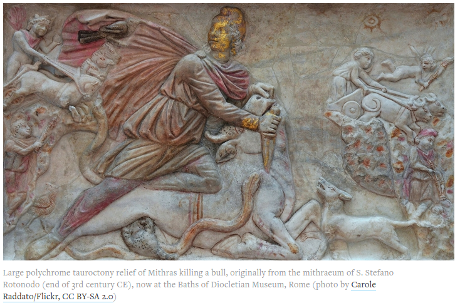

Modern technology has revealed an irrefutable, if unpopular, truth: many of the statues, reliefs, and sarcophagi created in the ancient Western world were in fact painted. Marble was a precious material for Greco-Roman artisans, but it was considered a canvas, not the finished product for sculpture. It was carefully selected and then often painted in gold, red, green, black, white, and brown, among other colors.

A number of fantastic museum shows throughout Europe and the US in recent years have addressed the issue of ancient polychromy. The Gods in Color exhibit travelled the world between 2003–15, after its initial display at the Glyptothek in Munich. (Many of the photos in this essay come from that exhibit, including the famed Caligula bust and the Alexander Sarcophagus.) Digital humanists and archaeologists have played a large part in making those shows possible. In particular, the archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, whose research informed Gods in Color, has done important work, applying various technologies and ultraviolet light to antique statues in order to analyze the minute vestiges of paint on them and then recreate polychrome versions.

Acceptance of polychromy by the public is another matter. A friend peering up at early-20th-century polychrome terra cottas of mythological figures at the Philadelphia Museum of Art once remarked to me: “There is no way the Greeks were that gauche.” How did color become gauche? Where does this aesthetic disgust come from? To many, the pristine whiteness of marble statues is the expectation and thus the classical ideal. But the equation of white marble with beauty is not an inherent truth of the universe. Where this standard came from and how it continues to influence white supremacist ideas today are often ignored.

Most museums and art history textbooks contain a predominantly neon white display of skin tone when it comes to classical statues and sarcophagi. This has an impact on the way we view the antique world. The assemblage of neon whiteness serves to create a false idea of homogeneity — everyone was very white! — across the Mediterranean region. The Romans, in fact, did not define people as “white”; where, then, did this notion of race come from?

…

A great post and reminder that learning history (or current events) through a particular lens isn’t the same as the only view of history (or current events).

I originally wrote “an accurate view of history….” but that’s not true. At best we have one or more views and when called upon to act, make decisions upon those views. “Accuracy” is something that lies beyond our human grasp.

The reminder I would add to this post is that recognition of a lens, in this case, the absence of color in our learning of history, isn’t overcome by our naming it and perhaps nodding in agreement, yes, that was a short fall in our learning.

“Knowing” about the coloration of familiar art work doesn’t erase centuries of considering it without color. No amount of pretending will make it otherwise.

Humanists should learn about and promote the use of colorization so the youth of today learn different traditions than the ones we learned.