This image came to mind while reading: Cebit 2015: Find out what your apps are really doing.

The story reads in part:

These tiny programs on Internet-connected mobile phones are increasingly becoming entryways for surveillance and fraud. Computer scientists from the center for IT-Security, Privacy and Privacy, CISPA, have developed a program that can show users whether the apps on their smartphone are accessing private information, and what they do with that data. This year, the researchers will present an improved version of their system again at the CeBIT computer fair in Hanover (Hall 9, Booth E13).

RiskIQ, an IT security-software company, recently examined 350,000 apps that offer monetary transactions, and found more than 40,000 of these specialized programs to be little more than scams. Employees had downloaded the apps from around 90 recognized app store websites worldwide, and analyzed them. They discovered that a total of eleven percent of these apps contained malicious executable functions – they could read along personal messages, or remove password protections. And all this would typically take place unnoticed by the user.

Computer scientists from Saarbrücken have now developed a software system that allows users to detect malicious apps at an early stage. This is achieved by scanning the program code, with an emphasis on those parts where the respective app is accessing or transmitting personal information. The monitoring software will detect whether a data request is related to the subsequent transmission of data, and will flag the code sequence in question as suspicious accordingly. “Imagine your address book is read out, and hundreds of lines of code later, without you noticing, your phone will send your contacts to an unknown website,” Erik Derr says. Derr is a PhD student at the Graduate School for Computer Science at Saarland University, and a researcher at the Saarbrücken Research Center for IT Security, CISPA. An important feature of the software he developed is its ability to monitor precisely which websites an app is accessing, or which phone number a text message was sent to.

At 11% of apps being malicious, you need spy on the spies that created the apps. Fortunately, Eric Derr and his group are working on precisely that solution.

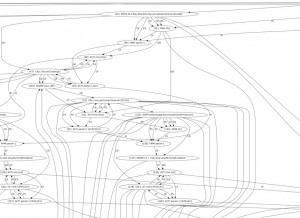

The CeBIT exhibition listing doesn’t offer much detail but does have this graphic:

The most details I could find are reported in: Taking Android App Vetting to the Next Level with Path-sensitive Value Analysis by Michael Backes, Sven Bugiel, Erik Derr and Christian Hammer.

Abstract:

Application vetting at app stores and market places is the first line of defense to protect mobile end-users from malware, spyware, and immoderately curious apps. However, the lack of a highly precise yet large-scaling static analysis has forced market operators to resort to less reliable and only small-scaling dynamic or even manual analysis techniques.

In this paper, we present Bati, an analysis framework specifically tailored to perform highly precise static analysis of Android apps. Building on established static analysis frameworks for Java, we solve two important challenges to reach this goal: First, we extend this ground work with an Android application lifecycle model that includes the asynchronous communication of multi-threading. Second, we introduce a novel value analysis algorithm that builds on control-flow ordered backwards slicing and techniques from partial and symbolic evaluation. As a result, Bati is the first context-, flow-, object-, and path-sensitive analysis framework for Android apps and improves the status-quo for static analysis on Android. In particular, we empirically demonstrate the benefits of Bati in dissecting Android malware by statically detecting behavior that previously required manual reverse engineering. Noticeably, in contrast to the common conjecture about path-sensitive analyses, our evaluation of 19,700 apps from Google Play shows that highly precise path-sensitive value analysis of Android apps is possible in a reasonable amount of time and is hence amenable for large-scale vetting processes.

One measure for security testing software is its confirmation of the findings of others and the making of new findings not previously reported. That has been reported for Bati but there is one malware case in particular that will be of interest.

Bati confirmed the malware reported by Symantec at: Android.Adrd, which mentions the malware driving page rank:

It also receives search parameters from the above URLs. The Trojan then uses the obtained parameters to silently issue multiple HTTP search requests to the following location:

wap.baidu.com/s?word=[ENCODED SEARCH STRING]&vit=uni&from=[ID]The purpose of these search requests is to increase site rankings for a website.

In addition to the baidu.com destination, other destinations were detected, including google.cn.

The only Symantec report that mentions google.cn, Backdoor.Ripinip is from March 15, 2012 and mentions it as a source of links for redirection, not building page rank.

The importance of spying on whoever is spying on you (and others) is only going to increase in importance.

Lawyers watching spies watching spies?