This man is trying to build Google Maps for the genome by Daniela Hernandez.

From the post:

The Human Genome Project was supposed to unlock all of life’s secrets. Once we had a genetic roadmap, we’d be able to pinpoint why we got ill and figure out how to fix our maladies.

That didn’t pan out. Ten years and more than $4 billion dollars later, we got the equivalent of a medieval hand-drawn map when what we needed was Google Maps.

“Even though we had the text of the genome, people didn’t know how to interpret it, and that’s really puzzled scientists for the last decade,” said Brendan Frey, a computer scientist and medical researcher at the University of Toronto. “They have no idea what it means.”

For the past decade, Frey has been on a quest to build scientists a sort of genetic step-by-step navigation system for the genome, powered by some of the same artificial-intelligence systems that are now being used by big tech companies like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, IBM and Baidu for auto-tagging images, processing language, and showing consumers more relevant online ads.

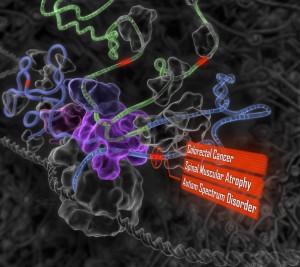

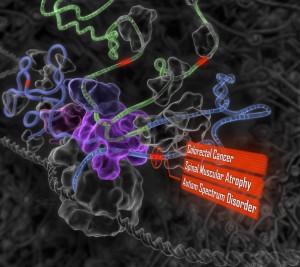

Today Frey and his team are unveiling a new artificial intelligence system in the top-tier academic journal Science that’s capable of predicting how mutations in the DNA affect something called gene splicing in humans. That’s important because many genetic diseases–including cancers and spinal muscular atrophy, a leading cause of infant mortality–are the result of gene splicing gone wrong.

“It’s a turning point in the field,” said Terry Sejnowski, a computational neurobiologist at the Salk Institute in San Diego and a long-time machine learning researcher. “It’s bringing to bear a completely new set of techniques, and that’s when you really make advances.”

Those leaps could include better personalized medicine. Imagine you have a rare disease doctors suspect might be genetic but that they’ve never seen before. They could sequence your genome, feed the algorithm your data, and, in theory, it would give doctors insights into what’s gone awry with your genes–maybe even how to fix things.

For now, the system can only detect one minor genetic pathway for diseases, but the platform can be generalized to other areas, says Frey, and his team is already working on that.

…

I really like the line:

“Ten years and more than $4 billion dollars later, we got the equivalent of a medieval hand-drawn map when what we needed was Google Maps.”

Daniela gives a high level view of deep learning and its impact on genomic research. There is still much work to be done but it sounds very promising.

I tried to find a non-paywall copy of Frey’s most recent publication in Science but to no avail. After all, the details of such a break trough couldn’t possibly interest anyone other than subscribers to Science.

In lieu of the details, I did find an image on the Frey Lab. Probabilistic and Statistical Inference Group, University of Toronto page:

I am very sympathetic to publishers making money. At one time I worked for a publisher and they have to pay for staff and that involves making money. However, hoarding information to which publishers contribute so little, isn’t a good model. Leaving public access to one side, specialty publishers have a fragile economic position based on their subscriber base.

An alternative model to managing individual and library subscriptions would be to site license their publications to national governments over the WWW. Their publications would become expected resources in every government library and used by everyone who had an interest in the subject. A stable source of income (governments), becoming part of the expected academic infrastructure, much wider access to a broader audience, with additional revenue from anyone who wanted a print copy.

Sorry, a diversion from the main point, which is an important success story about deep learning.

I first saw this in a tweet by Nikhil Buduma.